Living With the Leopard

Words Chelsea Johanes, Photographs and Illustrations Nick Sidle

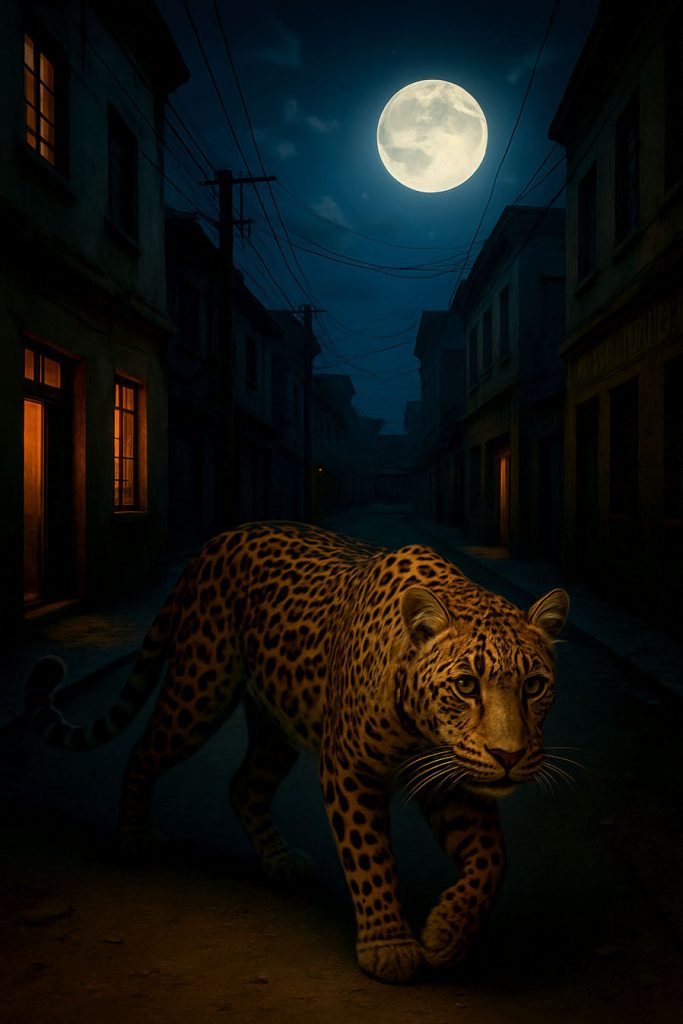

Photograph – Leopard, Panthera pardus, Serengeti

- The leopard is one of the big cats at up to 1.9m long (the tail adds another 50-95cm) and weighing 65-90kg.

- It is mostly solitary, lives up to 12 years in the wild and feeds on animals which can be bigger than itself and birds.

- The leopard is found in much of Africa and extensively in Asia.

- Camouflage, silence and stealth ending with a powerful short dash or pouncing from cover are its hunting strategies.

- The leopard’s senses are exceptional, hearing range is twice the human and in dim light when it typically hunts, sight is six times as effective. Leopards are mostly active at dusk and at night and rest in the day.

Digital illustration

- After a kill leopards, often drag their prey up into a tree to keep it from competitors such as lions and hyaenas. Both are stronger than a leopard individually and both operate in groups, which makes them a much bigger threat. The good news for leopards is that lions don’t climb trees, except for one population at Lake Manyara in Tanzania, and hyaenas just can’t. In India, in areas where there are no threats from other predators in the same way, leopards do not pull their kills up into trees at all.

Digital illustration

- The leopard’s strength is high, a 90kg young giraffe kill has been recorded as having been pulled up into a tree by a leopard.

- To people, especially children, leopards are a genuine threat, but incidents are few, far lower than with other big cats such as lions and tigers.

Digital illustration

- Bonds between female leopards and cubs are strong and reunions and sharing kills are seen even after separation.

- Leopards are highly adaptable and have even on occasion moved into areas of human settlement, including the outskirts of cities.

Digital illustration

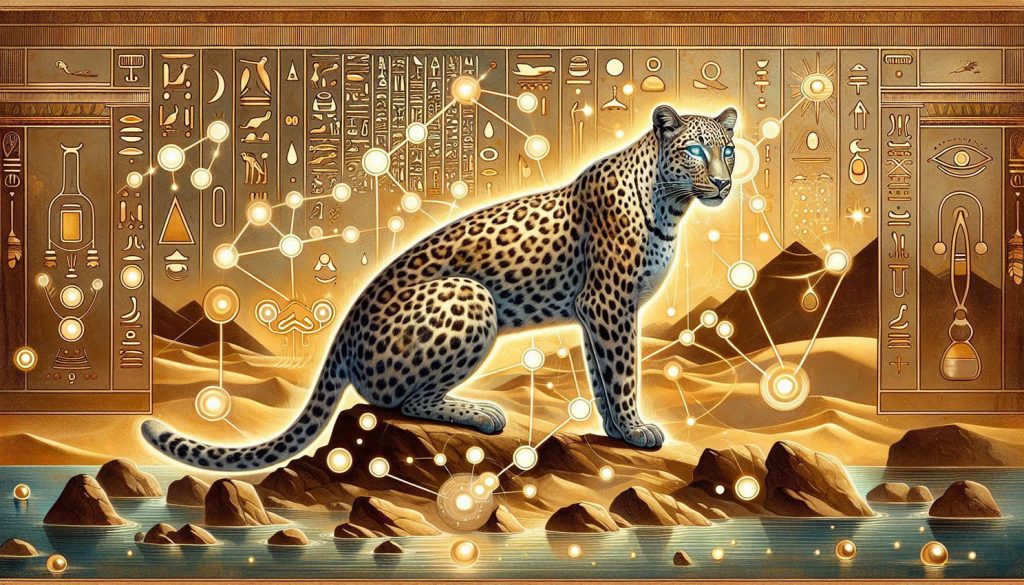

The Leopard – The Science of Silence and the Memory of Power

Chelsea Johanes, Kulture Konnect, Kenya

‘In the forests and riverside villages of western Kenya, a shadow moves with near-perfect silence. Rarely seen, yet always felt, the leopard (Panthera pardus) embodies patience, strategy, and quiet strength. Solitary and highly adaptable, it hunts mostly at night, relying on stealth rather than force, often carrying its prey high into trees to protect it from scavengers. Every step is deliberate, every movement measured,- a masterclass in survival shaped by observation rather than aggression.

Digital illustration

Leopards are often called silent guardians -not because they are passive, but because they are attentive. They watch. They assess. They react only when something else changes. This quality of restrained power is not only a biological trait, but one that has resonated deeply with human societies across time.

Digital illustration

What fascinates me is that this understanding of the leopard appears not only in African folklore, but also in ancient civilizations such as Egypt and Nubia. In these early knowledge systems, nature was not separated from science or philosophy. Animals were used as symbolic language to explain the behavior of forces and matter,- how something could remain dormant, controlled, and invisible, yet hold immense potential.

In early Egyptian proto-science and philosophy, animals often represented states of energy, reaction, and balance. One symbolic association my source once encountered linked the leopard to phosphorus-an element known for appearing stable and quiet until it comes into contact with another element, such as water, and suddenly reacts. Whether interpreted literally or symbolically, the meaning is powerful: silence does not imply inactivity. It implies readiness, potential.

Digital illustration

This same symbolism lives on much closer to home.

Among the Luo community of western Kenya, the leopard, kwach in Dholuo represents leadership, authority, and subtle power. Its image appears in oral traditions, praise poetry, and metaphors used to describe respected elders. Some elders have historically worn leopard skin as a marker of prestige and responsibility, signaling not dominance, but wisdom, restraint, and watchfulness. It is a living link between culture and ecology, one that continues to shape meaning today.

I remember visiting my aunt’s rural home in Muhoroni back in 2007. Children returning from the river would sometimes run home in panic after spotting a leopard nearby. Families planned their evenings carefully, eating dinner early and retreating indoors by six o’clock, aware that leopards began roaming freely at dusk. Similar stories echoed in Uyoma, Alego and many other places, quiet encounters in the night that inspired both fear and awe. More recently, a conversation with my art teacher brought back memories of his own encounters with leopards, reflections that revealed how deeply these animals remain embedded in Luo consciousness.

Digital illustration

In this way, the leopard exists at the intersection of ecology and human experience. It is a predator, yes- but also a symbol, a teacher, and a mirror of human values. Its nocturnal movements shape routines, influence storytelling, and dictate rhythms of daily life. It teaches communities about caution, awareness, and coexistence.

Scientifically, leopards are among the most adaptable big cats in Africa. They thrive in forests, savannas, grasslands, and even landscapes close to human settlements. Their varied diet ranging from small rodents to antelopes, allows them to survive in environments increasingly shaped by human expansion. Yet this adaptability also brings them into closer contact with people, creating moments of tension that demand understanding rather than fear.

Digital illustration

For the Luo, the leopard’s symbolism endures because it reflects a form of leadership grounded in restraint rather than force. It embodies patience, courage, and perception,- qualities echoed in community governance, storytelling, and moral instruction. To speak of the leopard is to speak of power that listens before it moves.

Through this story, we encounter the leopard’s dual existence: as a biological species navigating changing landscapes, and as a cultural symbol shaping identity, memory, and meaning. Its silent presence reminds us that the natural world is not separate from human knowledge, and that coexistence, whether in myth, memory, or reality, begins with observation and reverence.’

Digital illustration

Text ©Chelsea Johanes, photographs and Illustrations ©Nick Sidle, all rights reserved